Korean Air War 65 Years Ago

Lest We Forget

In January 1952 the Korean War was approaching the second anniversary of the invasion of South Korea by the North on June 25, 1950. Within days the first “provisional” elements of the 18th Fighter-Bomber Wing arrived from their base at Clark Air Base near Manila, and were thrown into combat to help save South Korea from being completely overrun by the superior North Korean forces.

In the popular mind, the air war in Korea was mostly dashing F-86 fighter pilots engaging in “dog fights” somewhere the near the Yalu River which serves as the border between North Korea and its neighbors, Russia (then USSR) and China. The reality was far more serious, and dangerous.

The primary mission of the 67th Squadron, one of four flying squadrons assigned to the 18th F-B Group, continued to be the “tactical interdiction of the enemy’s transportation system.” Commanding Officer Lt. Col. Julian Crow was directing most of his flights against railheads, communication lines and highways—all badly needed by the communists to move supplies and equipment to front-line positions.

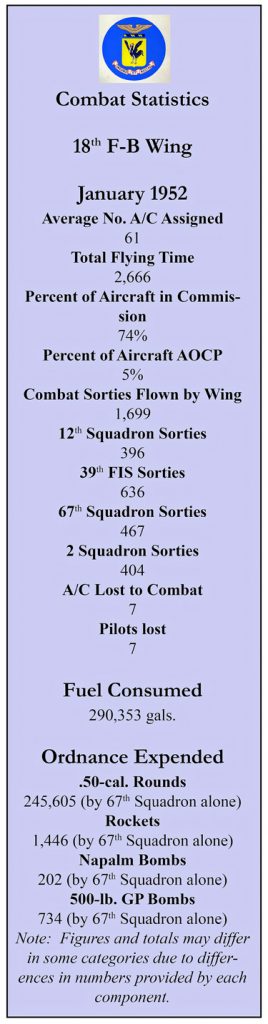

Numbers are dry, lifeless symbols that lack the excitement of strafing runs or bullets snapping past cockpits. However, the “numbers” reported by the 18th FBW give us a better understanding of how the Wing was supporting UN ground forces, the logistics that were required, and the priceless human lives it was paying to defend Freedom.

One of the seven pilots lost that month was 1st Lt. George Baylor Eichelberger, Jr., a 67th F-B Squadron pilot reported as KIA on 15 January 1952.

Lt. Eichelberger, a native of Norfolk, VA and a USMA graduate Class of 1950, was listed as MIA due to enemy ground fire while attempting to knock out transportation assets–his aircraft received a direct hit by anti-aircraft fire and crashed.

Lt. Eichelberger and Corporal Clarence Frownfelter whose assignment was in the 67th Orderly Room, “became very good friends. He was a Christian and was very open about it. He met with several of us for Bible Study and Prayer in the evenings. Included in these meetings were members of the 67th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, the 12th Fighter-Bomber Squadron and the Second Squadron SAAF.

I remember how our Squadron Commander [Lt. Col. Julian Crow] was affected the day that we lost Lt. Eichelberger. As it was with other pilots we lost, it was a very somber experience.”

In January, 2017 Frownfelter added to the story with this recollection.

“Julian Crow and I have maintained a close relationship through the years and in fact, I received a call from him in late January 2016. When I answered the phone, he started the conversation by saying, “Hello Clarence….this is the old crow” to which I replied, “Hello OLD Crow….where have you been lately?”

“He told me that he had just returned from a 3,000 mile trip, parked his car in the garage and came in to call me.” He further told me that “he had reservations for a 7 week cruise to Europe in April”. I told him for a man 99 years young, this was outstanding. Two weeks later, they found him deceased in his bedroom. Needless to say, the 18th FWA misses the Colonel.”

“Julian and I were talking about Eichelberger while in our reunion two years ago. He broke down in tears and related a story to me that I had never before heard. First thing he said to me was “Eichelberger was the best wing man I ever had” and added, “Did you know that when we arrived back at K-46 after Eichelberger ‘went in’, I fired up the L-19 parked on our flight line [Cessna L-19/O-1 Bird Dog, a liaison and observation aircraft], and flew back up to the crash site which was still burning to see if there was any possibility that Eichelberger had survived and with the intention of picking him up.” This was my Commander!”

“Not only was Col. Crow impressed with Eichelberger’s flying as his wing man,” Frownfelter continued, “but he made a lasting impression on Col. Crow as being a true Christian.” While describing Lt. Eichelberger to Frownfelter, Col. Crow placed his hand over his heart and recalled, “Eichelberger always carried his Testament in the pocket of his flight suit over his heart and was truly ready for what happened.”

Clarence Frownfelter currently serves as an officer in the 18th Wing Association.

Suggested citation:

Connors, T. D. (2007-2015). Salute to Lt George Eichelberger, USAF, Truckbusters from Dogpatch: the combat history of the 18th fighter-bomber wing in the Korean War, 1950-1953. Retrieved from BelleAire Press, LLC: http://www.truckbustersfromdogpatch.com/log-entries/salute-to-lt-george-eichelberger-usaf/

© Copyright 2017 BelleAire Press, LLC

Truckbusters

Truckbusters